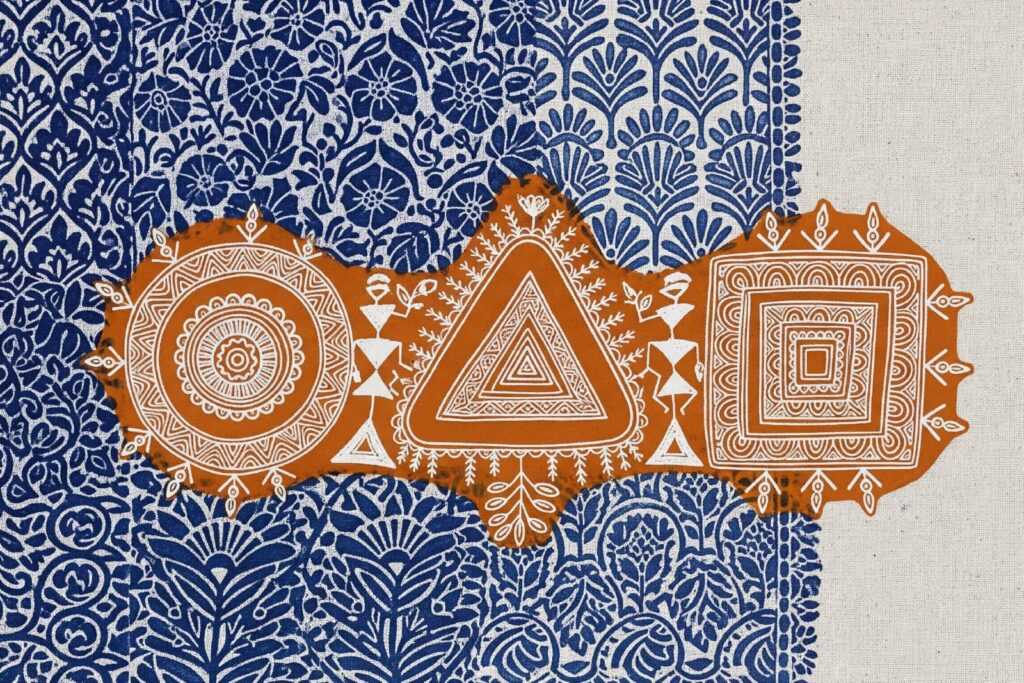

A circle, a triangle, a square. Three marks that once kept time with the monsoon songs of Maharashtra’s Warli villages now arrive in Mumbai’s glass towers as numbered editions.

The same economy that tried to scrub them off mud walls now underwrites their survival. Across India, art forms that were once mere footnotes in imperial ledgers are now transforming into salaries, protests, and runways. The goal is not nostalgia. It is the reclamation of narrative at full volume.

Colonial catalogues had a habit of freezing rivers into specimens. They labelled Kalighat pats as bazaar curios and filed Madhubani murals under “famine relief”. When the 1960s drought emptied Bihar’s fields, women moved the gods from courtyard walls to cheap cartridge sheets, trading ritual time for ration cards. Loss, it turns out, is only the prologue.

The quiet heroism of bureaucracy now plays its part.

A GI tag, that modest government seal, turns an anonymous craft into a passport. Bastar Dhokra, all twenty-seven careful steps of molten metal and riverbed clay, is suddenly a region speaking in one voice. Bagru’s indigo blocks, once interchangeable with any roadside print, now carry a postal address. Cheriyal’s narrative scrolls, thick with Telugu epics, refuse to be flattened into “Indian folk art”. The registry lists them like love letters to specific soils.

Numbers follow, but they are not cold.

Warli artists have sold over twelve hundred works in four years. One hundred and twenty-six bookmarks emerged from a prison workshop in Nashik, each tiny sheet a plea for time served and talent restored. Devram, who once painted walls for a meal, now signs canvases in confident Devanagari. The ledger records rupees and dignity in the same column.

In Kolkata, the story doubles back on itself.

After two centuries of exile in colonial albums, Kalighat brushstrokes have returned to the temple lanes where they first laughed at babus and courtesans. The 2024 precinct renovation bathes old gods and new satires in LED light. Tourists pose, phones flash, rent gets paid.

The Indian Museum hangs the original cat and mouse chase opposite a screen where the same cat now paces as an NFT. Heritage survives by learning new file formats.

Design schools have become unlikely shrines.

Nelly Sethna walked into Kalamkari villages in the 1970s with Scandinavian geometry and left behind revived blocks and living wages.

Today, Srikalahasti storytellers print solar eclipses onto linen shirts that travel in carbon-neutral boxes. The Ramayana is still told; only now it is whispered through the rustle of slow fashion.

Madhubani refuses to stay inside the sacred rectangle. Shalinee Kumari paints a menstruating goddess seated on a lotus of hashtags. Rani Jha turns bridal processions into protest marches against dowry. The same flat perspective that once flattened celestial mountains now flattens patriarchal excuses. Tradition becomes a megaphone rather than a cage.

Yet revival can sour.

A GI tag can shrink into a sticker. A curator can vacuum the breath out of a scroll.

The antidote is education, where children learn indigo fermentation alongside algebra, and where buyers meet dyers and count the hours folded into a single peacock motif.

Night falls over Kalighat.

The goddess on the temple wall glows under new lights, her lion pacing across screens worldwide. She once rode across postcards to amuse colonial officers. Tonight she rides again, paying school fees, court fines, and the rent on a studio where tomorrow’s stories are already mixing pigment. The circle, triangle, and square keep dancing. Only the walls have changed.